Elvis Presley completely dominated the screen in this film, but one strange detail about his hair slipped past almost everyone.

Few moments in pop culture feel as electric as watching a young Elvis Presley step into the spotlight for the first time without a microphone, without a roaring concert crowd, and without the safety net of being known only as a singer. Love Me Tender was not just his debut on the big screen. It was Hollywood freezing a moment in time, capturing raw momentum at the exact point when America’s newest obsession was transforming into a permanent cultural force.

Released in 1956, the film blends Western elements, family drama, and romance, all set against the uneasy emotional landscape left behind by the Civil War. For longtime fans, it feels like opening a time capsule. This is Elvis before the legend solidified, before the image became polished and untouchable. He still looks young, almost fragile, carrying a natural charisma that threatens to spill beyond the frame. For viewers coming in fresh, the movie often surprises. His screen presence is sincere, gentle, and far more restrained than many expect.

What’s easy to forget is that Presley didn’t arrive on set as a fully formed icon. He came as a phenomenon in motion. His records were selling at a staggering pace, crowds were growing louder and more frantic, and the public had already decided he was something new. Fame like that often flattens a person into a product. Yet nearly everyone who worked with him described the same thing: he was polite, modest, and deeply focused on doing the work well. He didn’t behave like a superstar lending his name to a project. He behaved like someone trying to earn his place.

His manager, Colonel Tom Parker, had a strategy that was clear and uncompromising. The movies would promote the music. Story mattered, but the soundtrack mattered more. These films were not designed to stretch Elvis as an actor. They were designed to keep him visible, profitable, and constantly in front of the public. Still, Elvis treated acting with respect. He reportedly memorized not only his own dialogue but his co-stars’ lines as well, the kind of preparation that suggests commitment rather than obligation.

Originally, the film was called The Reno Brothers, referencing the real-life Reno Gang, often cited as some of the earliest train robbers in American history. That grounding gave the story a historical anchor, though the script took plenty of liberties. Once the song “Love Me Tender” began gaining momentum, the studio pivoted. The title changed, aligning the movie with the hit, and the tone shifted. What might have leaned more heavily into postwar grit became a vehicle built around a rising star and a ready-made anthem.

Elvis plays Clint Reno, the youngest of four brothers. He is the one who stayed home during the war, the one who avoided battle, and the one forced to live with the fallout when the others return. The story revolves around familiar mid-century themes: loyalty strained by jealousy, love complicated by pride, and a family fractured by secrets carried home from conflict. Clint is asked to be tender in one moment and volatile in the next. He is not written as a deeply layered antihero, but the role carries enough emotional weight to show that Elvis could do more than smile and sing.

The premiere itself was closer to a cultural event than a standard screening. At the Paramount Theater in New York City, fans lined up, pressed against barricades, and screamed so loudly during Elvis’s scenes that much of the dialogue was drowned out. Contemporary accounts describe chaos. Teenagers fainted. Security struggled to maintain order. It was more than popularity. It marked a shift in how celebrity functioned in America, the birth of an intense fixation on presence, movement, and image.

What makes that moment even more compelling is Elvis’s long relationship with film before he ever starred in one. He had worked as a movie usher in Memphis, watching performers like James Dean, Marlon Brando, and Tony Curtis. He studied how they held emotion, how they conveyed intensity without overstatement. He wanted to be taken seriously on screen, not brushed aside as a novelty. That ambition was not always rewarded in later roles, but in Love Me Tender, the effort is visible in his focus and restraint.

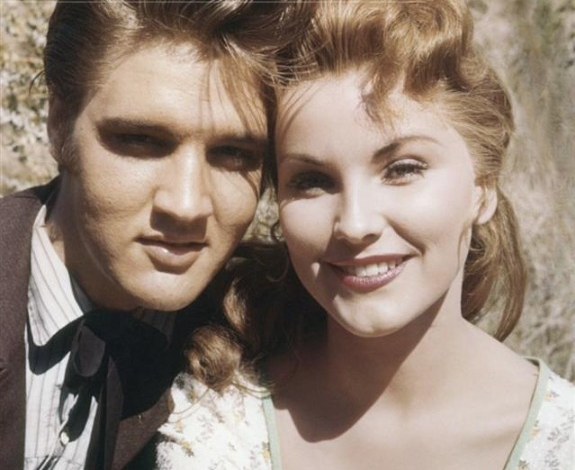

Much of the film’s warmth comes from the cast surrounding him, especially Debra Paget as Cathy. Paget was already gaining traction in Hollywood, and by some accounts, she arrived on set skeptical of the new singing sensation. Then she met him. Elvis, according to many recollections, won people over with old-fashioned courtesy, quiet confidence, and genuine respect, particularly toward her mother. Their chemistry on screen helps carry the romance even when the script edges toward melodrama.

The off-screen stories involving Paget have grown over time. Rumors circulated that Elvis was so taken with her that he considered proposing, only for her to decline, reportedly drawn to Howard Hughes instead. What is clearer is that her appearance in the film, especially her hairstyle, left a lasting impression. Years later, Priscilla Presley would draw inspiration from Paget’s look, a subtle thread connecting Elvis’s early Hollywood experiences to his later personal life.

One of the film’s strangest challenges is how it tries to exist in two eras at once. The story is set in 1865, but Elvis’s presence pulls it firmly into 1956. When he sings, the period bends. The songs do not feel like Civil War folk music so much as a modern idol stepping into historical costume and carrying contemporary magnetism with him. That tension is part of the film’s identity. It is both a Western drama and a record of a cultural explosion.

The title song itself has a layered past. “Love Me Tender” is adapted from “Aura Lee,” a ballad associated with the Civil War, reshaped into something softer and more intimate. Elvis performed it on The Ed Sullivan Show before the movie’s release, and the reaction was immediate. The song did not just promote the film. It became part of his public identity, something people could recognize instantly without remembering where they first heard it.

Then there is the detail fans still love to point out: the hair.

In the original script, Clint Reno dies, a bold choice for a debut film starring a rapidly rising idol. The story goes that Elvis’s mother, Gladys, was deeply distressed by the idea of audiences watching her son die on screen. To soften the ending, the filmmakers added a final image: Elvis’s silhouette singing “Love Me Tender” over the closing credits. It was meant to comfort viewers, allowing them to leave with music instead of grief.

That decision created a small but noticeable continuity oddity. In the closing silhouette, Elvis’s hair appears much darker, dyed black, compared to earlier scenes where it looks closer to his natural tone. It does not disrupt the story, but once noticed, it becomes irresistible, a brief glimpse behind the curtain where production choices peek through the illusion.

The film also contains the kind of classic Hollywood errors that make older movies feel tangible. A zipper appears where it shouldn’t. A modern car reportedly slips into frame. A guitar continues to sound after Elvis stops playing. A gun vanishes and reappears depending on the shot. None of these flaws undermine the film. They reinforce the feeling that you are watching a real artifact, assembled quickly to capture a moment that no one wanted to miss.

Few critics would argue that Love Me Tender is Elvis’s finest film. The narrative is simple, occasionally overwrought, and clearly designed to showcase its star. But as a piece of cultural history, it is invaluable. It marks the moment when the King of Rock and Roll crossed into Hollywood, when screaming fans followed him from the stage to the screen, and when you can still see the young man behind the legend trying to prove he deserved the space he occupied.

Watching it now is not just watching a movie. It is watching a turning point. An industry adjusting. A culture shifting. A young performer stepping into a new arena and learning, in real time, how to carry a name the world had already decided would endure.