Understanding a Common Body Response and Its Role in Urinary Health

Much of what keeps your body functioning well happens quietly, without conscious thought or effort.

You blink before your eyes dry out. You shift your posture before stiffness sets in. You yawn to recalibrate focus. You feel thirsty before dehydration becomes dangerous. None of these reactions are accidental. They are built-in safety systems designed to maintain balance with minimal input from you.

Because these signals feel automatic, people often dismiss them. Small urges are brushed aside as inconvenient, postponed for later, or treated as awkward topics better left unspoken. Over time, however, repeatedly ignoring the body’s basic cues can lead to real consequences—recurring discomfort, higher infection risk, and health problems that were largely preventable.

One frequently misunderstood example is the urge to urinate after close physical intimacy. Many people—particularly women—notice it soon after, sometimes within minutes. It may feel inconvenient, embarrassing, or even concerning. Some ignore it. Others wonder if it signals a problem.

In most cases, it doesn’t.

More often than not, it’s your body doing exactly what it’s designed to do: protecting your urinary system.

The quiet intelligence behind automatic signals

Your body relies on interconnected systems working in the background at all times. The nervous system monitors pressure and sensation. The kidneys filter blood and regulate fluid levels. The immune system stays alert for bacteria. Muscles in the bladder, urethra, and pelvic floor contract and relax to manage urine flow and maintain stability.

You don’t consciously coordinate any of this. You simply receive the message: It’s time to go.

After physical closeness—especially when it involves movement, pressure, and pelvic muscle engagement—several normal changes occur simultaneously. Blood flow to the pelvic area increases. Muscle tone shifts. Nerve sensitivity rises. Hormones associated with relaxation and bonding circulate. All of this is normal and temporary, part of how the body responds to stimulation and then resets itself.

During that transition, the bladder and urethra often receive a gentle mechanical prompt. The result is a familiar sensation: the need to urinate.

It’s not a disruption. It’s guidance.

Why the urge often appears after intimacy

Anatomy plays a major role. The bladder sits low in the pelvis, close to other structures involved in sexual activity. Movement and pressure in that region can slightly compress the bladder, even if it isn’t particularly full. Nerves that transmit sensation from pelvic organs may interpret this stimulation as a cue to empty.

At the same time, arousal and physical exertion can subtly influence how the kidneys filter fluids. Some people produce urine a bit faster during and after arousal. Combined with hormonal changes that affect muscle relaxation and tone, the outcome is entirely predictable: the urge to urinate.

This response doesn’t mean there’s a problem. It doesn’t indicate poor bladder control or weakness. It’s a normal physiological reaction involving blood flow, muscle activity, nerve signaling, and pelvic pressure.

The protective role of urinating after intimacy

What many people don’t realize is that urinating after physical closeness isn’t only about comfort—it can actively help protect against urinary tract infections (UTIs).

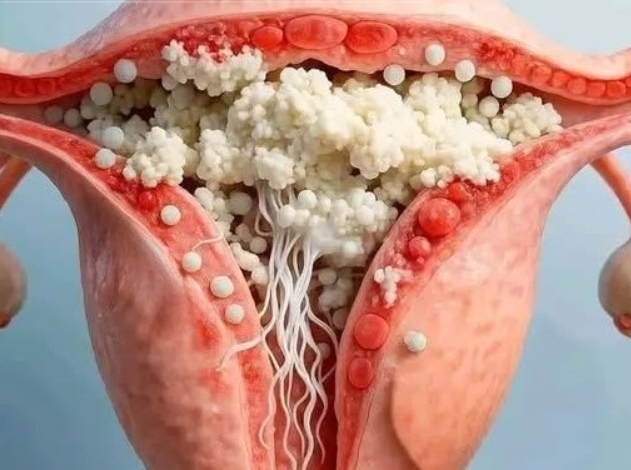

UTIs occur when bacteria enter the urethra and travel upward toward the bladder. Once bacteria attach to the urinary tract lining, they can multiply and cause symptoms such as burning, urgency, pelvic pressure, or frequent urination with minimal output.

The bacteria most commonly responsible for UTIs normally live harmlessly in the digestive tract. They aren’t “dirty” or abnormal—they’re simply out of place when they reach the urinary system. During intimacy, friction, body contact, and anatomical proximity can allow bacteria to move closer to the urethral opening.

Urinating helps flush the urethra, pushing potential bacteria out before they have time to settle and travel upward. It’s not a guarantee against infection, but it significantly reduces risk, particularly for people who experience UTIs repeatedly.

Why women face higher risk—and why prevention matters

Women are more prone to UTIs because of basic anatomy. The urethra is shorter, and its opening is closer to areas where bacteria are more common. That shorter distance makes it easier for bacteria to reach the bladder.

This isn’t a flaw—it’s simply biology. But it does mean that preventive habits matter more.

Simple actions can have a disproportionate benefit, and urinating after intimacy is one of the easiest and most effective steps. It takes seconds, costs nothing, and supports the body’s natural defenses.

Comfort and tissue recovery: an overlooked benefit

Beyond infection prevention, urinating after intimacy can also improve overall comfort. After arousal and physical activity, pelvic tissues are often more sensitive due to increased blood flow and stimulation. Passing urine clears residual fluid from the urethra and helps the area return to its baseline state more smoothly.

It’s not only about bacteria—it’s also about easing irritation and supporting recovery after friction and pressure.

That’s why many people feel noticeably better afterward: less tense, less uncomfortable, and more settled.

Changes in urine appearance afterward

Some people notice lighter-colored urine or a different smell after intimacy. In most cases, this is harmless. Urine color and odor vary based on hydration, diet, and concentration levels. Temporary changes in how your body processes fluids can affect appearance without indicating any issue.

What matters more than how it looks is responding to the urge. When your body signals the need to urinate, consistently delaying it rarely helps.

The cost of ignoring the signal

Holding urine for extended periods can create an environment where bacteria multiply more easily. If bacteria have already entered the urethra, delaying urination gives them more time to move upward.

Occasionally holding urine won’t automatically cause an infection, but making it a habit—especially after intimacy—can increase risk, particularly for people who are already susceptible.

Certain conditions can heighten vulnerability. Diabetes, for example, can affect immune response and urinary health, making infections more likely and harder to resolve. Dehydration, specific medications, and other health factors can also play a role.

This is why basic advice often proves reliable: listen to your body.

Make it part of a broader urinary health routine

Urinating after physical closeness works best when combined with other supportive habits:

Stay well hydrated so your body produces urine regularly. Frequent urination is one of the urinary tract’s natural cleaning mechanisms.

Avoid harsh soaps, scented products, and aggressive cleansing in sensitive areas, as irritation can disrupt natural protective barriers.

Choose breathable fabrics, especially if you’re prone to irritation or infections.

Pay attention to persistent symptoms. Burning, pain, fever, back pain, blood in urine, or ongoing urgency should be evaluated by a medical professional rather than ignored.

The goal isn’t anxiety—it’s awareness.

Letting go of stigma around basic body functions

Many people avoid talking about urination, hygiene, or UTIs because it feels uncomfortable. That silence fuels confusion, shame, and misinformation around something completely normal.

Needing to urinate after intimacy is common. It’s not strange. It’s not embarrassing. It’s not a sign something is wrong with you.

It’s a protective reflex—your body helping clear the urinary tract and lower infection risk.

Small habits, lasting benefits

Good health isn’t built only through dramatic decisions. It’s built through small, repeatable actions that quietly reduce risk over time. Peeing after intimacy is one of those actions: simple, quick, and surprisingly effective.

Listening to your body isn’t overthinking—it’s basic self-care. When you understand why these signals exist, you stop treating them as inconveniences and start recognizing them as the guidance system they were always meant to be.