Three Convicts Were on the Way to Prison

The prison bus creaked and rattled along the empty highway under a dull, gray sky, carrying three men toward the same destination and three very different kinds of regret. The engine groaned with each mile, the metal benches vibrated under them, and the smell of diesel mixed with stale coffee and resignation. None of them spoke at first. Each was lost in thought, knowing that whatever freedom they had before this moment was now locked behind steel doors and razor wire.

As part of intake, they had one small concession: each prisoner could bring a single personal item—something harmless, something to occupy time in a place where minutes stretched endlessly. That small allowance suddenly felt precious.

The silence broke when the man nearest the aisle shifted and glanced at the others. He was lean, sharp-eyed, someone who seemed like he always had a plan, even when everything went wrong.

“So,” he said casually, as if they were strangers on a long road trip rather than men bound for prison, “what did you bring?”

The man beside him, older and broader, reached down and pulled a small cardboard box onto his lap. Opening it carefully, he revealed neatly arranged tubes of paint and brushes worn soft with use.

“I brought paints,” he said with unexpected pride. “I’ll paint anything they let me—walls, rocks, scrap wood. Might as well come out with something to show for it. Who knows, maybe I’ll be the Grandma Moses of cell block D.”

He chuckled at his own joke and turned to the first man. “And you?”

The first man pulled a deck of cards from his bag, flipping it expertly between his fingers. His grin suggested he’d won more than he’d lost in life, even if losing had brought him here.

“Cards,” he said. “Poker, solitaire, gin rummy, blackjack. You can play a hundred games if you’ve got time. And trust me, I’ll have time.”

They both turned to the third man, who had been quiet all ride, arms folded, a slow, satisfied smile on his face. He looked far too pleased for someone heading to prison.

The painter raised an eyebrow. “Alright, what about you? You’ve been grinning since we left. What’s in your bag?”

The third man pulled out a box and held it up like a trophy.

Tampons.

The other two stared, waiting for the punchline.

“You serious?” the card player asked. “What are you supposed to do with those?”

The third man didn’t rush to explain. He simply smiled wider, tapped the box, and said, “According to the instructions, I can go horseback riding, swimming, roller-skating, and pretty much live my best life.”

For a moment, silence. Then laughter filled the bus, so loud even the driver peeked in the mirror. By the time the gates swallowed them and the bus rolled away, that laughter was the last taste of real freedom they would feel that day.

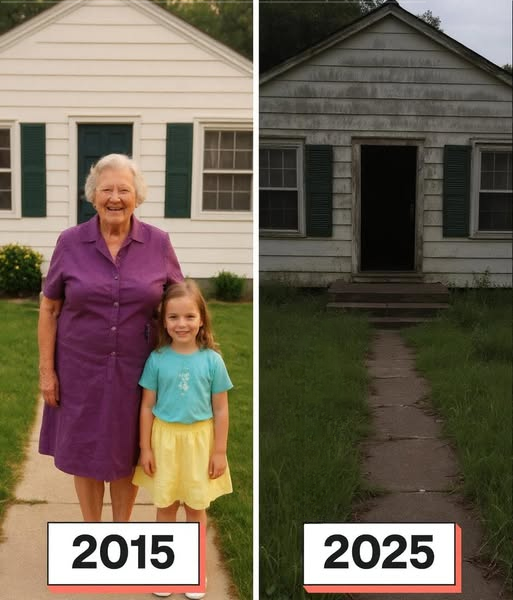

Prison life settled in fast.

Days blurred together—count, meals, work assignments, lights out, repeat. For the first-timers, the hardest part wasn’t the confinement itself but learning the rhythm without asking too many questions.

One man quickly realized that prison had its own culture, language, and brand of humor.

His first night was the hardest.

Lights snapped off all at once, plunging the corridor into shadows pierced only by thin slashes of moonlight through narrow windows. The air was thick with whispered conversations, the clink of bunks, and a distant cough.

Then a voice rang out.

“Number twelve!”

Laughter erupted across the block. Men slapped bunks, wheezed, hooted, and howled as if they’d never heard anything funnier.

The new guy sat up, confused.

A few minutes later, another voice shouted, “Number four!”

The laughter followed—just as loud, just as uncontrollable.

“What’s going on?” he asked his cellmate, an older inmate with a face carved by time and experience.

“We’ve all been here long enough that everyone knows the same jokes,” the older man said. “So instead of telling them over and over, we just number them. Saves time.”

The new guy frowned. “So they just yell a number, and everyone knows the joke?”

“Exactly,” his cellmate said.

The new guy paused, then an idea sparked. He waited for a lull, then stepped forward and shouted, “Number twenty-nine!”

For half a second, silence. Then the cell block exploded. Men fell off bunks, gasping for air, laughing harder than ever. Even a guard shouted for quiet.

When it finally subsided, the new guy turned to his cellmate.

“I don’t get it,” he said.

The older man wiped tears from his eyes. “We’d never heard that one before.”

And just like that, the new guy understood prison humor better than any orientation manual could explain.

Life inside didn’t become easy. It was still loud, cramped, repetitive, and unforgiving. But humor—dark, absurd, ridiculous—became currency, a way to remind oneself of humanity in a place designed to strip it away.

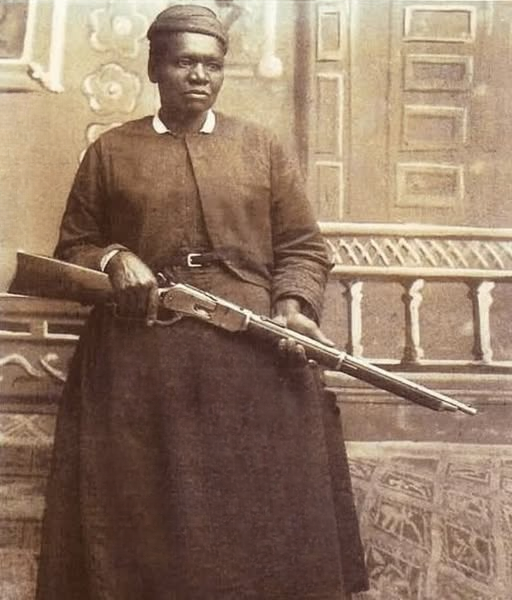

The man with paints became known for his artwork, covering scraps of wood with landscapes no one had seen in years. The card player ran games through long nights with shuffles and quiet bets of favors instead of money. And the man with the tampons? He never stopped smiling, even when nothing else made sense.

Because sometimes, the only freedom left is the freedom to laugh.